Imagine holding a small carved bowl, its weight and shape and size a perfect fit for two cupped hands. The grain of the wood flows with the bowl’s curves, the interplay of light and dark pleases the eye, the texture is silken against your skin. You turn it, admiring the craft, the artistry, the attention to detail.

“It’s lovely,” you say, handing it back to its creator. “Now when are you going to make something real, like furniture?”

Now imagine the bowl is a short story.

Why do so many readers—and writers—consider short fiction to be some sort of training wheels? As if writing a short story is just a way to wobble around until you find your balance and center of linguistic gravity and are ready for the big-girl-bike of a novel?

Sigh.

Short stories are my favorite art form. A good one is compact and complete, a telling little slice of life, capturing a moment in time that—for the character—defines her, changes her, is the tipping point for all that will follow. Picture yourself walking down a street at dusk, passing by an open front door. Perhaps you see a family at dinner, arguing. Perhaps you see a brief kiss. Just a sliver of a stranger’s life before you walk on. That house will never be the same for you.

When I write, I try to capture one of those pivotal moments. If I succeed, I have shifted the reader’s view of the world, just a little. The character is not the only one to experience change.

That is my job, shifting perceptions, one story at a time.

The trouble is, I don’t like writing.

But I love having written.

At the beginning of a story, I have only the glimmer of an idea. A line of dialogue, a character, a setting, a time period. I think about it. It settles in my brain, nestles—or nettles—like a tickle or an itch. It often sits like that for a very long time.

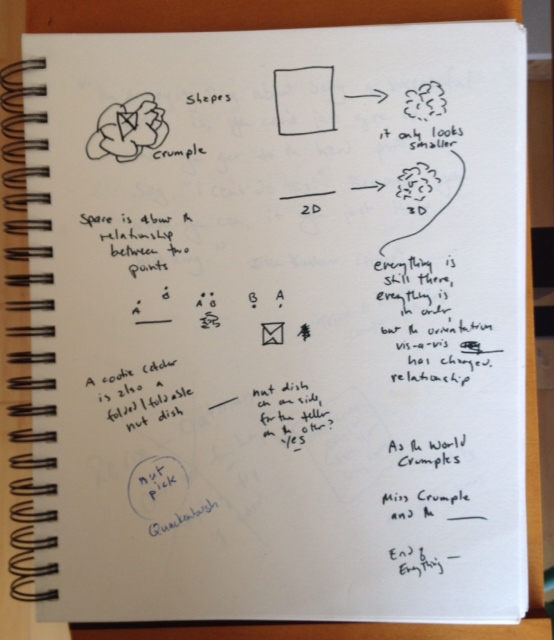

My process is messy and non-linear, full of false starts, fidgets, and errands that I suddenly need to run now; it is a battle to get something—anything—down on paper. I doodle in sketchbooks: bits of ideas, fragments of sentences, character names, single lines of dialogue with no context. I play on the web as if Google was a pinball machine, caroming and bouncing from link to link to tangent, making notes about odd factoids that catch my eye.

I am a writer, and writers are magpies. Ooh! Shiny! Some of those shinies are distractions, but others are just the right size or shape for me to add to the jumble of flotsam and fragments that I am slowly building into a mental nest where I will—I hope—hatch a story. I gather scraps until that amazing moment when a few of them begin to coalesce into a pattern.

My father once told me that I have a mind like a lint trap—I pull stuff out of everything, and a lot of it just clings. Many of my stories crystallize around some vividly remembered detail: the smell of the basement in the house I grew up in; the way the light slanted across the lawn of my best friend’s house when it was time to go home for dinner; the incendiary, sticky texture of the hot vinyl backseat of my mother’s Ford convertible against my bare, damp legs.

Layers of tiny, precise detail accrete. Like a coral reef, or knitting a scarf out of strips of whimsy.

Eventually, I have to put some words down onto paper. Readers expect stories to have words, in some sort of coherent order. But this is a painful chore, and I avoid it, procrastinating desperately until the deadline looms too close to ignore.

I try. These words are awful. Boring, clichéd, stilted. I can no longer write a coherent sentence. I despair.

Of course, first drafts always suck. I know this, and I forget it every time. (In the back of my mind, I still believe that Hemingway sat down at his typewriter, wrote A Farewell to Arms, and then sauntered off to have lunch.)

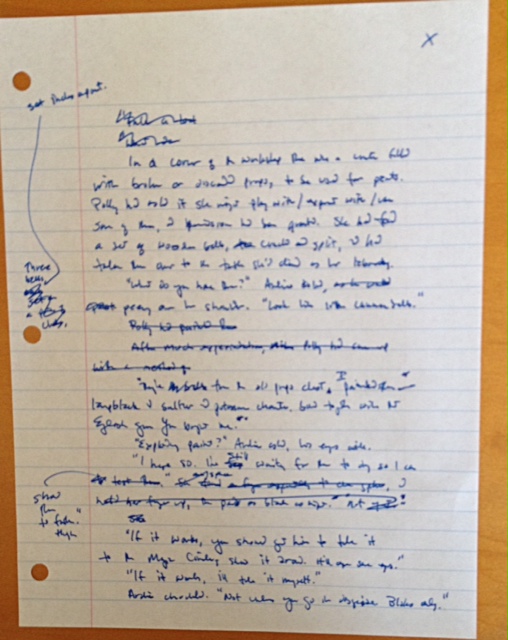

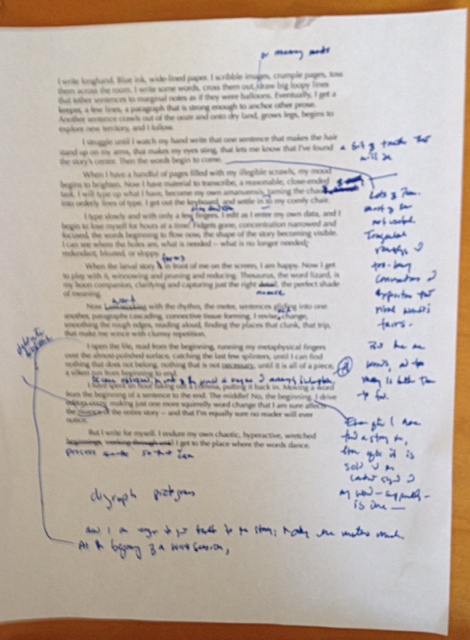

About my first drafts: I write longhand. Bold ink, wide-lined paper. I cannot create on a keyboard. I scribble images, crumple pages, toss them across the room. I make some pictograms, cross them out, draw big loopy lines that tether sentences to marginal notes as if they were zeppelins. Eventually, I get a keeper, a few words, a paragraph that is strong enough to anchor other prose. Another sentence crawls out of the ooze and onto dry land, grows legs, begins to explore new territory, and I follow.

I struggle until I watch my hand write that one sentence that makes the hair stand up on my arms, that makes my eyes sting, that lets me know that I’ve found a bit of truth that will be the story’s center.

Then the words finally begin to come.

In torrents.

I fill page after page of blue-lined sheets, the pile growing until my hand aches and I look up and discover it is dark outside and I don’t remember if I had lunch.

Many of these words are not useful. They are irrelevant ramblings and too-long, too-boring dialogues in which characters just chat. There are huge paragraphs that are exposition to rival world’s fairs.

But they are words, and too many is so much better than too few.

Once I have a handful of pages filled with my nearly illegible scrawls, my mood begins to brighten. Now I have material to transcribe, which feels like a very reasonable, manageable task. All I have to do is type up what’s already there, become my own amanuensis, taming the chaos into orderly lines of print.

I can do that.

I get out the keyboard, and settle into my comfy chair.

(Note: Although I have taken typing classes—twice—it is so not one of my skills. I type slowly and with only a few of my available fingers, and even then it is tedious and full of errors and I spend a lot of time backspacing.)

But this gives me ample opportunity to edit as I enter my own data. I begin to lose myself for hours at a time. Fidgets gone, concentration narrowed and focused, the characters are beginning to breathe, the shape of the story becoming visible. I can see where the holes are, what is needed—and what is no longer needed: redundant, bloated, or sloppy.

As the larval story forms in front of me on the screen, I find myself grinning. I am happy. At last I get to play the writing game, winnowing and pruning and reducing. Thesaurus, the word lizard, is my boon companion, clarifying and capturing just the right nuance, the perfect shade of meaning.

I work with the rhythm, the meter, sentences gliding into one another, paragraphs cascading, narrative connective tissue forming. I revise and change, smoothing the rough edges, reading aloud, finding the places that clunk, that trip, that make me wince with clumsy repetition.

I love this last stage of a short story. I feel like Julia Child making a sauce. I reduce and reduce, intensifying the “flavor” of the prose. I become obsessed, the rest of the world a vaguely annoying interruption. Dishes pile up, emails go unanswered, vegetables turn to protoplasm in the fridge.

I’m almost there. I back up every fifteen minutes, and if leave the house, the story is on a thumb drive in my pocket.

So close. (As is the deadline, usually.) I wake up eager to open the file, read from the top, running my metaphysical fingers over the almost-polished surface, catching the last few splinters, until I can find nothing that does not belong, nothing that is not necessary, until it is all of a piece, a silken run from beginning to end.

When do I know a story is finished? When the last line feels inevitable. Not predictable (I hope), but the moment when the door to that stranger’s house closes, leaving the reader satisfied, but also musing and pondering.

Then I read it aloud one more time, catching a few last clunks, and send it out.

And I am done! I do the Dance of Completion, open a bottle of wine, flop onto the couch and watch TV without guilt.

Done!

Or not. I always re-read a story again a day or two later, partially because I want to reassure myself that I really can still do this, and partially because it’s like a new puppy and I just want to pat it now and then.

In general, I think, I am pleased. I like this story. Well, mostly. There is that one sentence….

No, Klages. Back away from the story.

But I can’t.

Once, after a story was sold, and the contract signed, I spent an hour taking out a comma, putting it back in. Moving a word from the beginning of a sentence to the end, then back to the beginning. I frequently drive editors crazy, even at the copy-edit stage, making just one more squirrelly change that I am sure affects the delicate balance of the entire story—and that I’m equally sure no reader will ever notice.

My editors are very patient.

But every word counts. And I endure my own chaotic, hyperactive, wretched process, so that I can get to that place where the words dance for me—and me alone—before I let it out into the world.

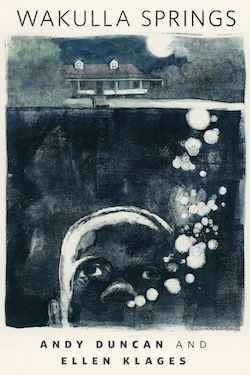

The exception to this is “Wakulla Springs,” which I wrote with my dear friend Andy Duncan. It is the only time I have attempted to collaborate, and the process was very different.

For one thing, it took ten years.

I had a glimmer of an idea, a file full of related clippings, some notes for a story that involved Tarzan and monsters and Florida myths. But I could not find the nugget of story in all of it. One night, I realized that it really ought to be an Andy Duncan story, and I had no idea how to write one of those. I admire and goggle and worship at the feet of Andy’s storytelling. I just don’t have a clue how he does it.

So, in 2003, at a convention, I bought Andy a beer, and regaled him for an hour about all the minutiae in my file and in my head, telling him of my suspicion that a story was lurking in there somewhere.

Andy is as good a conversationalist as he is a storyteller, and soon we were swapping ideas and possibilities, gesturing madly and getting excited about imaginary things in a way that only writers can do and still appear reasonably sane. I offered to send Andy the file and let him run with it. He countered that we ought to write it together.

Huh? Oh. Okay, sure. I think?

A year later, same convention, we sat down with another round of beers and had more animated conversations and started talking about characters and a four-act structure. We made notes. (This was counter to either of our usual methods, but we figured it might be useful to believe we were working on the same project.)

Andy’s process is a lot like mine, I think, because for seven years we chatted about the story and made some more notes and did some research, but neither of us wrote any actual words.

Then in 2010, in a last-ditch effort to try and produce something, we flew to the panhandle of Florida for a week. We intended to lock ourselves in the hotel suite, write 1500 words a day, each, and have a solid draft of the story knocked out by Saturday.

This did not happen.

We walked around Wakulla Springs, the setting for the story, and took notes and pictures. We spent two afternoons in the Florida State Archives reading through boxes of WPA interviews and local folklore. We connected Andy’s laptop to the hotel TV and watched DVDs of Tarzan and Creature movies every night.

And we talked, pretty much non-stop. We talked about our shared passions for fantasy in real life, for movies, and monsters, and heroes, swamps and myths and legends. About the scary things that we almost believed in as kids, and how that shaped us. We talked about story and character over very good barbecue, interrupting with a lot of “Hey! What if…?”

We created a shared world and walked around in it, pointing out the sights to each other, tourists in a land no one else could see.

Then we went home to write. A week, we figured. A month, tops.

It took two-and-a-half years. I followed my own arcane writing process, and 3000 miles away, Andy did the same. We didn’t talk on the phone or email or consult, but every few months, one of us would have finished enough of a draft of a scene to send to the other and say, “Whad’ya think?”

We made suggestions and edits. We added to each other’s scenes, suggested what characters might—or might not—do, and we each offered the other amazing narrative gifts. The whole became so much more than the sum of its parts.

(I found out later that Andy was thinking about my style and the way I build characters as he wrote, while in my head I was hearing dialogue and exposition read in Andy’s lovely and distinctive drawl.)

We fixed some plot holes over beers at Readercon in 2012, and vowed to have the piece finished by the end of the year. Andy gave me the onerous honor of the last editing pass, because the story had originally been my idea. That phase was not very different than finishing up a solo piece: I smoothed rough places, moved some bits around, made some picky word choices. I altered some of my own syntax to match Andy’s cadence, and reworked some of his sentence structure to match mine. By the end, we had 35,000 words that sounded, even to our own ears, as if they’d been written by one person.

The grain of the words flows, the interplay of light and dark pleases the eye , the texture of the descriptions are silken and pleasing to the ear. I am immensely proud of the craft that went into it, the artistry, the attention to detail.

And yet, “Wakulla Springs” is a rather odd bowl. Andy and I chose such exotic woods and carved into it such arcane themes and such eccentric shapes that I have heard many protest, loudly and vociferously, that they do not think it really qualifies as a bowl at all.

The words do not always dance to a song you have heard before.

And that is why I write.

Ellen Klages is an American science fiction, fantasy, and historical-fiction writer born in Columbus, Ohio in 1954. She began publishing short fantasy and SF stories in 1998; her novelette “Basement Magic” (2003) won a Nebula Award. In 2006 she published her first novel, The Green Glass Sea, a middle-grade novel set in Los Alamos during World War II; it won the Scott O’Dell Award for Historical Fiction. Portable Childhoods, a collection of her short fiction, appeared in 2007. Her Hugo-nominated story “Wakulla Springs,” co-authored with Andy Duncan, is available to read for free here on Tor.com.